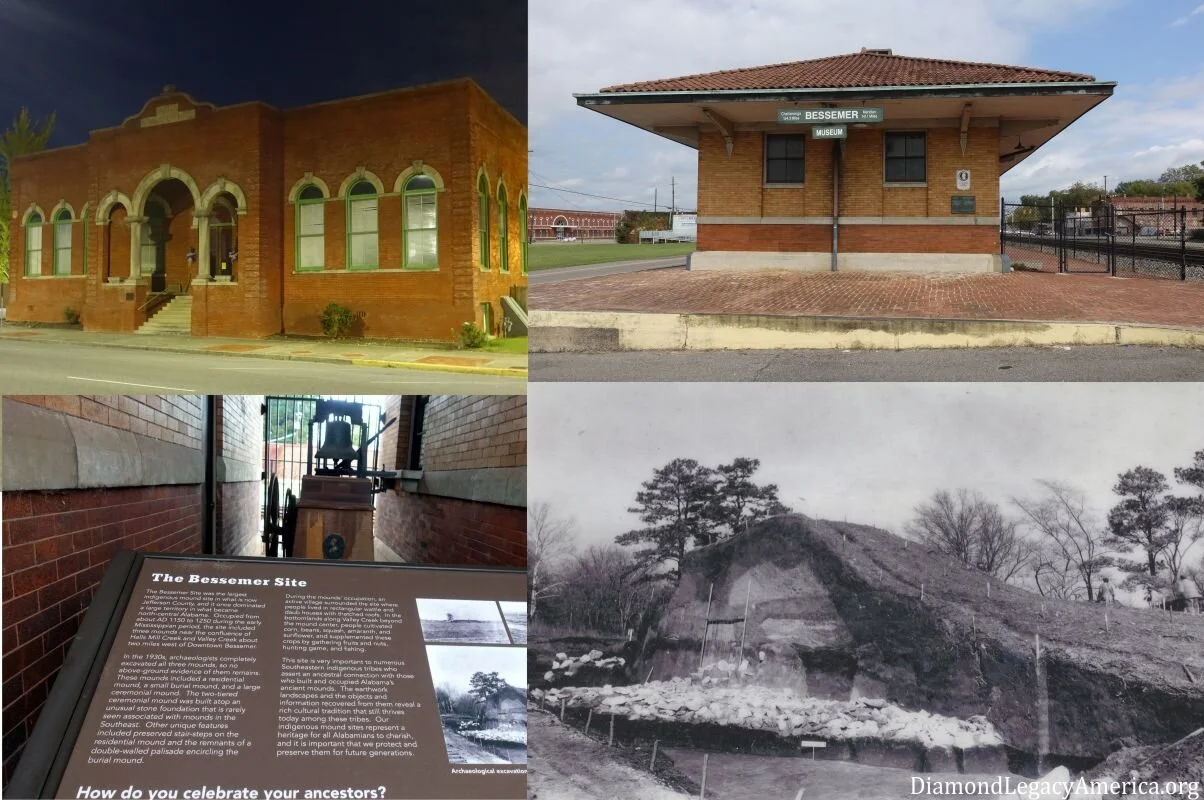

Aboriginal Mound Site – “Bessemer, Alabama”

Images and signage at “Bessemer, Alabama“ for the Aboriginal Mound Center

While joyously appreciating that Alibamu (or Alabama Territory) has so much natural beauty, we spent the early morning hours at two spectacular locations that were in close proximity to our planned destination. Both the Historic Coke Ovens Park and the Cahaba River WMA (Water Management Area) are near the “town of West Blocton.”

After a while, we realized our bodies were both thirsty and hungry, so we went to find something to satisfy these needs before returning to the route off “US-11” on the way to a “town” called “Bessemer.” We were looking for the Hall of History Museum located on “Alabama Avenue” where signage was placed to identify an Aboriginal Mound Site that was completely destroyed during excavations in the 1930s.

The museum occupies a building that was once the “Alabama Great Southern Railroad-Bessemer Depot.” originally constructed in 1916 as ordered by the “Railroad Commission.” Early photos of the building, measuring 170 feet long by 70 feet wide, present the same curb appeal observed today—quite an attractive design and it is listed on the Register of Historic Places.

Arriving at the museum, we noticed how close the structure sits to the railroad tracks and a fence separates them. We were disappointed to find out that the museum is closed on Mondays. It may be a good idea to check schedules before-hand, especially in small towns like this one. Reportedly, there are artifacts, cultural information and materials, and historic industry related exhibits contained inside, which might have included additional details about the mound site.

An important objective of our many Journeys of Appreciation is to honor the Legacy of First Nation People and to experience wondrous connectivity with our ancestors. We are determined to know where the site is actually located and whether any other signatures are present. We, especially, want to find the essential water source—a strategic feature of Aboriginal homesites.

About the Aboriginal Mound Site

From displayed signage, we cite the first paragraph that claims: “The Bessemer Site was the largest Indigenous mound site in what is now Jefferson County, and it once dominated a large territory in what became north-central Alabama. Occupied from about AD 1150 to 1250 during the early Mississippian period, the site included three mounds near the confluence of Halls Mill Creek and Valley Creek about two miles west of Downtown Bessemer.”

And another paragraph proclaims that “an active village surrounded the site where Indigenous People lived in rectangular wattle and daub houses with thatched roofs. In the bottomlands along Valley Creek beyond the mound center, people cultivated corn, beans, squash, amaranth, and sunflower, and supplemented these crops by gathering fruits and nuts…”

Absent of personal observance, our further research of published sources (archaeological and ethnological) revealed details about these Aboriginal wonders, such as—they were:

referred to as the “Talley” Mounds, a.k.a., “Tally” Mounds, “Bessemer” Mounds, or “Jonesboro” Mounds;

located in a “town” called “Jonesboro” that was established in 1813 and said to be one of the earliest settlements in “Jefferson County” or present-day “Bessemer;

part of the village area, containing the three mounds, that was fully excavated in the 1930s by a “University of Alabama Museum of Natural History” archaeological team led by D. DeJarnette, who used unskilled “New Deal Program” laborers and thus shares responsibility for the rampant destruction of these monuments built on sacred ground;

described as valuable demonstrations of the so-called Late Woodland-Mississippian period containing hundreds of artifacts, many displaying vessel shapes of “grog-tempered and shell-tempered” pottery; and

documented evidence of Aboriginal habitation includes: a) remains of a young female placed in the “Ceremonial Mound” during construction; and an earlier village with post holes evincing many rectangular structures and additional burials, including a dog, was found below the base of this mound; b) a “Burial Mound”, reportedly, containing 23 total burials constructed in stages; c) a “Domiciliary Mound” was evidently built in six stages with ramp steps to the top and more structures were found below this mound; and,

reportedly, “several single-component occupations by people who made mostly plain-surface, grog-tempered pottery” were found during excavation at the “West Jefferson Steam Plant” and revealed carbon-dating of AD 900 to 1060.

Also, we noted during research on the topic that several large commercial operations took unjust actions on Aboriginal Land. The “Alabama Splash Adventure Amusement Park” opened in 1998, after formerly being known as “Visionland Theme Park.” And the “WaterMark Place Shopping Center” opened in 2000.

After going through survey reports, information on related mound sites, and statements presented by compassionate locals, it is hard to fathom what would compel anyone to continue to rummage through obvious Aboriginal possessions and—more importantly—to desecrate their ancestral graves. There was (and still is) much vacant natural land available in the Americas, which actually signifies the heritage and vast estate of First Nation People. After arrival of minority groups (emigrants/immigrants from Europe), the land was and still is being stolen and usurped by means of unscrupulous treaties and policies established to show favoritism for their own growth and prosperity at the expense of the lawful Heirs. These words are meant to calmly evoke truthful awareness.

The three mounds have been destroyed on the Land; however, they will forever exist in our hearts and memories as we continue to honor Aboriginal Legacy in the Alibamu Territory.

Water Resources Nearby – Valley Creek and Halls Mill Creek

Scenic image of Valley Creek at “Hueytown, Alabama”

From the museum location, we asked a few locals how to get to these two creeks; they knew about Valley Creek yet were unfamiliar with the other one. Based on their directions, we made many attempts until finally used GPS directions to the “Valley Creek Water Treatment Facility” located on Clearwater Drive. We had no information about it; and latter research did not confirm its relationship to the previously mentioned excavation site. Eventually, we observed signage denoting ‘Valley Creek Bridge’ and stopped for an amazing photo opportunity, featuring gorgeous blue skies over dense forested shorelines, beautifully mirrored on the water. What a memorable experience.

It is also said that Valley Creek begins under downtown “Birmingham Alabama” and flows west to the Black Warrior River. Its watershed covers about 257 square miles and becomes part of many cities, including, “Bessemer, Hueytown, Brighton and Fairfield”.

As previously stated, the settlement of “Jonesboro” was located on the banks of Halls Creek near the confluence with Valley Creek (southwest of downtown Bessemer). Reportedly, it was the first colonial settlement in what was referred to as the “Jones Valley” located at the southern end of the foothills of the Appalachian Mountain chain. It is said to serve as a watershed between the Black Warrior and Cahaba Rivers, where we have observed mounds at Moundville respectfully.

We appreciate witnessing that Aboriginal People, who inhabited this area, enjoyed an abundance of water resources on bountiful land.

Valley Creek to include vegetation and trees at “Hueytown, Alabama”

“Town of Bessemer”

Navigating through this “historic town” on at least two occasions, we saw plenty of things to talk about. Here are a few interesting experiences:

Right away we were surprised that the majority of people around “town” were of Moorish American descent, which correlates to the 2016 survey declares that 70.8 percent of 28,636 population identified themselves as “African American,” Admittedly, we get excited to be in communities where most businesses are owned and neighborhoods are full of people who look like us. It would be especially rewarding if they are “awake” and no longer accept these derogatory assigned names.

At times we find ourselves in local libraries and museums looking for information to complement our research about the area. On this occasion, we went to the Library on 19th Street and were turned away because the so-called mask wearing policy was “pushed” by staff and security personnel “doing their jobs” (or so they seemed to think).

While strolling one evening, we noticed an attractive brick building with similar features of Moorish designs, and engraved at the top was ‘1907 Library.’ Also, there is a marker identifying it as the “Bessemer Chamber of Commerce.” Closer observation shows signage acknowledging a grant from the “Carnegie Foundation” and a “resolution” establishing the “Bessemer Carnegie Library” which is at the corner of “18th Street and 4th Avenue”. After years of temporary moves, renovations, and expansions, the renamed “Bessemer Library” transformed into the state-of-the-art facility mentioned above that now rests on “19th Street.”

We also observed The Bright Star Restaurant, which claims to be the oldest restaurant in Alabama (locally owned and operated more than 100 years). The large red neon star on the building caught our attention from down the street and inside the lobby was tasteful wall decor consisting of nostalgic photos, artwork, news articles, and other memorabilia. The gracious hostess checked to see what plant-based meal options were available and other than salads or side items—there were none. We decided not to dine yet enjoyed the experience.

In addition to its early habitation by Aboriginal People, “Bessemer” has a fascinating past:

Reportedly, in 1886, it was founded by an industrialist who was said to own iron and coal businesses. Over the years this new “town” (named after the man who operated the most prevalent steel manufacturing process) experienced rapid growth and the economy was based mostly on mining and steel production. Afterall, it was located within the “Jones Valley” which is said to be rich in iron ores needed for steel making. In 1907, TCI (Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company) was a major employer and they sold stock to “U.S. Steel” to assist with mounting debt during the recession. We observed one of the massive “U.S. Steel” operations recently while traveling between “Bessemer” and “Fairfield.” Reportedly, following the decline in the mining and steel industry in the twentieth century, the city started to diversify its economy. Hence its nickname…“The Marvel City.”

“Downtown Bessemer, Alabama

“City of Fairfield”

Initially, we traveled to “Fairfield” due to its similarities with “Bessemer” – both “towns” arose out of necessity to capture the growing steel manufacturing industry and to boost economy in the area. Research sources claim that they ultimately became competitors with “Fairfield” claiming victory because of its close affiliation with the “City of Birmingham.” It seems that being a part of its “Metropolitan area” helped immensely and reportedly, steel manufacturing was banned in “Bessemer”…though some related iron ore businesses still operate and contribute to the thriving economy of “The Marvel City.”

Upon leaving Fairfield, we were startled by the large display sign denoting “Miles College” (established in 1898) where the road led into a quaint neighborhood nestled along rolling hills and intertwining streets. And judging from the people observed outside their homes, the majority were so-called African Americans. We continued navigating along until we arrived at a different entry point that seemed quite familiar.

As a matter of fact, we observed other parts of the college campus earlier as we enjoyed an afternoon stroll around the charming “downtown” area, i.e., old building structures; patrons browsing through wares on sidewalks in front of business locations, and time was well spent at an attractively designed “community park” located near a baseball field, where we delighted at witnessing many mature trees and plant variations. Our attention shifted when Jamal noticed large clusters of brownish-colored mushrooms snuggling the ground around a towering tree (possibly oak). One cluster was so large that it was almost smothering an ant hill. Appreciating the stone architectures featured on two pillars at the baseball field and the uniquely patterned artwork on the centerpiece at the park, we enjoyed the walk back to the main street.

In summary, our goal of honoring the Legacy of First Nation People was achieved through this Journey of Appreciation that documents great ingenuity and strategic planning as evidenced by the numerous mounds and villages established on the mineral-rich lands along the Valley Creek and many other connecting waterways at Alibamu Territory.

We hope you enjoy reading about our experiences and will start creating your own memorable journeys.

Peace

images of “Fairfield, Alabama”